Text: Glyn Demmer

The differential lock is commonly known in the off-roading fraternity as a “locker” – and essentially it is a variation of a standard, open differential, as employed in all vehicles.

Here’s how it works. An axle has two side shafts joined to the differential that are driven by the differential gears inside the differential casing. This set-up allows wheels to rotate at different speeds when negotiating corners. The open diff provides the same torque (twisting or rotational force) to each wheel – but the gearing allows a different rotational speed.

In other words, by way of example, in a left-hand turn the differential will slow down the left-hand rear wheel, allowing the right-hand outside wheel (which has less traction) to cover the greater radius. This also prevents what is known as tyre scrubbing or scuffing, when both wheels turn at the same rotational speed around corners.

But in an off-road environment, this is a drawback. When a wheel loses traction, more rotational speed is sent to the wheel with the least resistance, which is the wheel that has already lost traction. This causes the wheel that has lost traction to spin even more, without gaining any traction. At this point you are generally, well, stuck.

This is where the differential lock comes in. It overcomes the limitation by locking both wheels, allowing them to turn together regardless of the traction lost. This enables the wheel with traction to pull you through the obstacle.

Engagement may be electronic, pneumatic or hydraulic. As a rule you will engage the locker before entering the obstacle if you were able to assess the situation correctly. In other words, reading the line you have to take to conquer the obstacle.

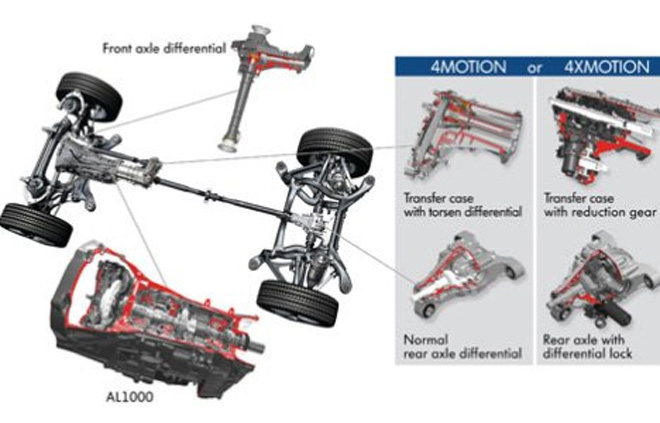

The same principle applies to lockers fitted to front and rear axles, as well as the centre lockers fitted to a full-time four-wheel drive vehicle. In the latter case, the open centre diff prevents “wind-up” between the front and rear axles, and it is only locked (manually) when the vehicle goes off-road.

“Wind-up” occurs when a four-wheel drive vehicle, with a locked centre differential, is driven on hard surfaces such as tar. Small differences in the rotational speed between the front and rear wheels cause torque to be applied across the transmission. This can lead to considerable damage to a transmission or drivetrain. On slippery surfaces these differences are absorbed by the slippage of the tyres on the loose surface.

One gets selectable lockers which are generally fitted as original equipment by most manufacturers. These are traditionally engaged by a switch, normally fitted on the dashboard or centre console. The benefits are better drivability when used as an open locker, with on-demand locking capability.

Lockers are particularly useful when axle articulation is limited (in vehicles with independent suspension set-ups, for instance).

Leaving the locker engaged after conquering an obstacle will put the drivetrain components and tyres under tremendous strain. So rather don’t do that.

Locking differentials, such as the ones fitted as standard to, say, a Toyota Hilux, are engaged via a hydraulic system. Some after-market versions, designed for rough-and-tough 4×4 applications, are operated by compressed air. For example, ARB’s pneumatic Air Lockers use a 12-volt air compressor designed to activate and deactivate a locking mechanism inside the differential, to provide a 100% locking solution.

The LSD option

Limited-slip differentials (LSDs) are something of a compromise. They operate automatically with a smooth action directing additional torque to the wheel with traction. Yes, they provide more traction than an open differential in 4×4 conditions, but the vast majority of these systems, especially the factory-fitted ones, don’t provide the full lock of a traditional differential lock — more like 40-60%, on average.

These systems are mostly a passive on-road (tar and dirt) safety feature, and they will operate only when slip is sensed.

For more hardy off-road conditions, some companies do provide after-market limited slip differential systems that feature full lock capability. The advantage of such a system is that the driver doesn’t need to bother about locking differentials before entering an obstacle. The system sorts itself out while you tackle the obstacle, and locks when it needs to lock.

But these systems are normally quite noisy, and are also harder on tyres. So they are not ideal for occasional off-roaders, but are aimed more at the hardcore 4×4 gang.

While the limited slip differential has been employed in two-wheel drive performance cars for decades, the technology has become a popular piece of kit for road-going four-wheel drive vehicles in recent times.

Mainstream brands such as Audi, for instance, uses the technology for its quattro range of passenger four-wheel drive vehicles.

There are different types of limited slip diffs, too. Limited slip systems can be divided into two groups: the torque sensing system and the speed sensitive system.

The torque sensitive systems consist of gears or clutches, while the speed systems feature viscous or pump and clutch pack technologies.

Ultimately, though, if you plan on tackling serious 4×4 tracks, the traditional limited slip differential’s application is indeed limited. A normal differential lock will serve you better.

But times have changed, and with 4x4s increasingly relying on technology to pull them through the tough stuff, the traditional role of the limited slip differential is now very much entwined with the age of the computer.

An increasing number of modern vehicles employ electronic traction control systems, sometimes in tandem with a rear differential lock. These systems use wheel sensors coupled to a central processing unit (CPU) to monitor wheel speeds.

If wheel slip is sensed, the traction control system momentarily brakes the slipping wheel, transferring power to the wheel that has traction. Many of these systems use ABS (anti-lock braking) to perform this function.

In essence, though, the computer performs the function of a limited slip differential.

There are, of course, many different technologies used by car companies. In Porsche’s PSD system, for instance, a computer monitors wheel slip and regulates the amount of lock in a mechanical limited slip differential through electro-hydraulic control.

Mitsubishi’s Active Yaw Control (AYC) system, on the other hand, uses a conventional open rear differential, fitted with an added planetary gear set. The computer monitors various parameters, including wheel slip, and when it deems it necessary to intervene, it can increase the torque sent to one wheel through a hydraulic clutch pack.

In the end

The limited-slip’s applications are more focused on road usage, where it provides more sure-footed traction, especially in slippery conditions. On a dirt road, for instance, the limited slip differential aids traction, and it works really well. Much like an electronic traction control system, really.

But if you plan on tackling the extreme Baboons Pass 4×4 track in Lesotho, or even milder 4×4 tests, a traditional differential lock still rates tops.