By Narina Exelby and Mark Eveleigh

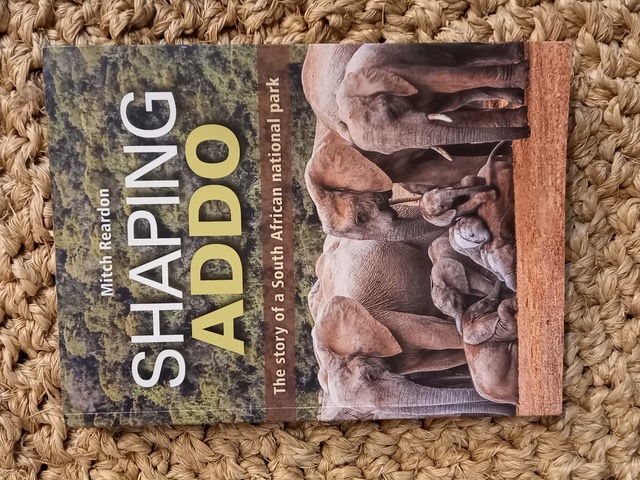

Whenever we hit the road, we pack a small library of reference books into the double-cab – and two of our favourites, particularly when we visit national parks, are Shaping Kruger and Shaping Addo, by wildlife writer and photographer (and ex-ranger) Mitch Reardon. Don’t be mislead by the titles – these books are insightful reference books for anyone with an interest in African wildlife.

Shaping Addo (published 2021) is an intriguing portrayal of a protected area that has become so much more than just an elephant park so we asked author Mitch Reardon to clue us in on some unexpected aspects of Addo that are likely to surprise even regular visitors.

1. Addo’s biodiversity is astounding

Stretching from the near-desert Nama Karoo in the north, across the Zuurberg mountain range and south to the extremely high conservation status islands in Algoa Bay, Addo is the most ecologically diverse protected space in South Africa. The park includes five of South Africa’s seven biomes (distinct botanical communities), including extensive and near-impenetrable spekboom thickets that are found only in a small area in and around the park.

2. More than half of SA’s bird species are found in Addo

Addo’s diverse habitats account for its extraordinarily profuse range of bird species – approximately 450, nearly half the South African total and far more than any other African national park. That’s because birds are found in habitats that vary from arid near-desert, to large bodies of fresh water, tall indigenous montane forests, open grasslands, thickets and coastline.

3. See the world’s largest colony of gannets

Algoa Bay’s Bird Island and St Croix Island provide sanctuary to the world’s largest breeding colony (nearly 200,000) of Cape gannets and the planet’s largest breeding colony of endangered African penguins. The bay’s open waters host pelagic marine species such as albatrosses, petrels, skuas and shearwaters.

4. Addo has grown – a lot

At just 2,240 hectares Addo was the smallest national park in southern Africa in 1931. These days it is about 130 times that size and – with a population that is estimated to be somewhere between 650 and 700 – it is home to the highest concentration of wild elephants anywhere in the world.

5. See a dung beetle with a difference

There are over 800 different dung beetle species in South Africa but only one flightless dung beetle, and it’s endemic to Addo and its immediate surrounds. It doesn’t occur outside the spekboom zone and it was precisely those thickets that shaped its flightlessness. At some point in their evolution they dispensed with flight because they lived in thick vegetation and no longer needed wings. In their closed world flight was superfluous.

6. Lions behave differently in Addo

In the Kalahari, lions maintain prides as they do in all big, open range African parks. Once they were released into Addo’s relatively small southern section they adopted a unique social system in which adult males form coalitions, usually of two, and lionesses live apart with their cubs. Another interesting aspect of lion behaviour occurred when these apex predators met Cape buffaloes. How the two adapted to the other’s sudden appearance is another Addo phenomenon that fascinated scientists and laymen alike. Neither species had any experience of the other because buffaloes don’t occur in the Kalahari and the last indigenous Addo lion was shot some 175 years earlier.

Pictures: Narina Exelby and Mark Eveleigh